At the end of the section of his letter to the Corinthians dealing with "the Lord's table", Paul wrote: "Therefore, whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord" (1 Cor 11:27).

What is it to eat in "an unworthy manner"? Some Christadelphians have used this verse to defend their idea of "guilt by association" and as a reason for denying the bread and wine ('Communion') to people who do not share the same doctrinal distinctives, and even to other Christadelphians who disagree on doctrinal details.

In the context of the Corinthian division between rich and poor (see previous message) it seems certain that in Paul's mind to eat or drink "in an unworthy manner" would be to do so in such a way that our Lord's teachings about bringing together all classes and types of people (characterised by His pattern of 'table fellowship') were ignored. The Corinthian rich treated the poor with contempt, and so their meal was 'not the Lord's supper' according to Paul.

Any religious service, regardless of whether or not 'Communion' or 'breaking of bread' is a feature, if it flies in the face of our Lord's inclusiveness by denying participation to any member of the Body of Christ, is 'not the Lord's supper'. There is no reason to think that a mere token consumption of a morsel of bread and a sip of wine is 'the Lord's Supper', especially if it is based on exclusivism and denies access to anyone.

In fact, those Christadelphians who are exclusive in their fellowship practices may themselves be guilty of eating and drinking "in an unworthy manner". To celebrate breaking of bread "without recognizing the body of the Lord" is to bring judgment on ones self. Paul is saying that those who are 'in Christ' are the body of Christ and must be treated in love.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

The Lord's table (12) - the Last Supper was no ordinary meal

The last supper was obviously no ordinary meal. So what was so special about it, why was it different, and how, and what are we meant to learn from it?

It's clear that the last supper was the Passover meal - certainly no ordinary meal - which was meant to remind Israel of their deliverance from Egypt. Our Lord re-interpreted it as a celebration of our deliverance from evil. Even aside from the fact that this was a special meal in Israel's calendar of feasts and commemorations, the Lord knew that this was to be no ordinary meal: "I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer" (Luke 22:15). John explains further: "It was just before the Passover Feast. Jesus knew that the time had come for him to leave this world and go to the Father. Having loved his own who were in the world, he now showed them the full extent of his love (John 13:1).

In hindsight we know that this was to be a special meal for the Lord because it was to be his last meal before his death. He asked that it be commemorated "in remembrance of me", although He did not specify how, or how often. Some denominations commemorate the Last Supper once a year, at Passover (and 1 Cor 5:6-8 may suggest that early Christians celebrated the Passover annually as a Christian Festival). Some celebrate it daily; others weekly or quarterly. Some Christians celebrate it whenever they get together.

In the absence of any clear instructions in the Bible about this, the church has had to rely on tradition and the scant evidence in the Bible and early Christian writings about the practices of the early church. Luke tells us that the practice of the early Jerusalem church was to meet for "the breaking of bread" and "they broke bread in their homes", apparently daily (Acts 2:42-47). In Troas they met "on the first day of the week" (Acts 20:7). In Corinth a collection was made on the first day of the week and it's reasonable to suppose that a church meeting took place on the same day and that this is when they had the meal which Paul describes in 1 Cor 11:17-34. The only detailed account we have received is this record in 1 Corinthians, which was part of Paul's correction of certain abuses in the church. If the Corinthians hadn't been celebrating the Lord's Supper in "an unworthy manner" we would have had no information at all about the tradition of the early church.

Meals in first century Judaism.

For the Jews in general every meal was 'religious' in the sense that it was accompanied by the giving of thanks to God. Jewish daily meals began with a prayer of thanksgiving associated with the breaking of bread, and concluded with a further prayer of thanksgiving ("grace before meals" and "grace after meals" are still elements of the daily meals of the orthodox). Wine was included in weekly sabbath meals and on special occasions, and there is some evidence that a prayer was said over each cup of wine.

At the last supper the eating of the bread and the drinking of wine was separated by the meal (see for example the words "after the supper he took the cup" in Luke 22:20 and 1 Cor 11:25), and a prayer for said for each, corresponding with grace before and after meals.

The Lords Supper in Corinth

In the Hellenistic (Greek-speaking) world it was common among the wealthy for meals with invited guests to be in two stages: the main meal was eaten first, followed by a "symposium" which consisted of desserts and drinks, accompanied by speeches and discussion. Some guests would be invited for the first stage, and further guests would be invited to the symposium. (There is also some evidence that on some ocasions the symposium was 'open' for anyone who was not invited but who wished to listen to the speeches and discussion to stand around the outside, although not joining in the desserts and drinks).

The main problem in Corinth arose out of tensions between the rich and poor. For the first few centuries of Christianity meetings were held in homes and not in church buildings. The size of meetings was dictated by the size of the largest home. Obviously meetings would therefore usually be in the homes of the wealthiest members. This seems to have been the case in Corinth. While we don't know exactly what was going wrong in Corinth, we do know that a distinction was being made between rich and poor. There are two main possibilities:

In the earlier messages I've written in this series I think it's been clear that there is a pattern in the way the Gospel-writers record the meals where our Lord was present. Either by example or through His words the Lord taught that meals should reflect the abundant generosity and graciousness of God. We should invite to our tables the poor, the sick, the disabled, the 'sinners', the 'unclean' and the disenfranchised. They should be places where we celebrate and share the forgiveness of God, and look forward as a kind of foretaste to the messianic banquet in the age to come. The Corinthian practice created a division in the church between the rich and poor, which was contrary to this message of Jesus. It was therefore not "the Lord's supper" because it went so violently against the spirit of His message.

The Lord's table was inclusive; the Corinthian table was exclusive. The Lord's table brought together people from opposite ends of the social spectrum; the Corinthian table created a division in the Body of Christ. The Lord's table celebrated forgiveness. The Corinthian table created envy. The Lord's table proclaimed His self-giving, demonstrated in His death; the Corinthian table was self-centred. At the Lord's table people examined themselves; at the Corinthian table they judged each other.

In determining how the Lord intended us to "do this", and in deciding how the church today should celebrate the Lord's Supper, we should keep in mind these important factors:

It's clear that the last supper was the Passover meal - certainly no ordinary meal - which was meant to remind Israel of their deliverance from Egypt. Our Lord re-interpreted it as a celebration of our deliverance from evil. Even aside from the fact that this was a special meal in Israel's calendar of feasts and commemorations, the Lord knew that this was to be no ordinary meal: "I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer" (Luke 22:15). John explains further: "It was just before the Passover Feast. Jesus knew that the time had come for him to leave this world and go to the Father. Having loved his own who were in the world, he now showed them the full extent of his love (John 13:1).

In hindsight we know that this was to be a special meal for the Lord because it was to be his last meal before his death. He asked that it be commemorated "in remembrance of me", although He did not specify how, or how often. Some denominations commemorate the Last Supper once a year, at Passover (and 1 Cor 5:6-8 may suggest that early Christians celebrated the Passover annually as a Christian Festival). Some celebrate it daily; others weekly or quarterly. Some Christians celebrate it whenever they get together.

In the absence of any clear instructions in the Bible about this, the church has had to rely on tradition and the scant evidence in the Bible and early Christian writings about the practices of the early church. Luke tells us that the practice of the early Jerusalem church was to meet for "the breaking of bread" and "they broke bread in their homes", apparently daily (Acts 2:42-47). In Troas they met "on the first day of the week" (Acts 20:7). In Corinth a collection was made on the first day of the week and it's reasonable to suppose that a church meeting took place on the same day and that this is when they had the meal which Paul describes in 1 Cor 11:17-34. The only detailed account we have received is this record in 1 Corinthians, which was part of Paul's correction of certain abuses in the church. If the Corinthians hadn't been celebrating the Lord's Supper in "an unworthy manner" we would have had no information at all about the tradition of the early church.

Meals in first century Judaism.

For the Jews in general every meal was 'religious' in the sense that it was accompanied by the giving of thanks to God. Jewish daily meals began with a prayer of thanksgiving associated with the breaking of bread, and concluded with a further prayer of thanksgiving ("grace before meals" and "grace after meals" are still elements of the daily meals of the orthodox). Wine was included in weekly sabbath meals and on special occasions, and there is some evidence that a prayer was said over each cup of wine.

At the last supper the eating of the bread and the drinking of wine was separated by the meal (see for example the words "after the supper he took the cup" in Luke 22:20 and 1 Cor 11:25), and a prayer for said for each, corresponding with grace before and after meals.

The Lords Supper in Corinth

In the Hellenistic (Greek-speaking) world it was common among the wealthy for meals with invited guests to be in two stages: the main meal was eaten first, followed by a "symposium" which consisted of desserts and drinks, accompanied by speeches and discussion. Some guests would be invited for the first stage, and further guests would be invited to the symposium. (There is also some evidence that on some ocasions the symposium was 'open' for anyone who was not invited but who wished to listen to the speeches and discussion to stand around the outside, although not joining in the desserts and drinks).

The main problem in Corinth arose out of tensions between the rich and poor. For the first few centuries of Christianity meetings were held in homes and not in church buildings. The size of meetings was dictated by the size of the largest home. Obviously meetings would therefore usually be in the homes of the wealthiest members. This seems to have been the case in Corinth. While we don't know exactly what was going wrong in Corinth, we do know that a distinction was being made between rich and poor. There are two main possibilities:

- The rich were arriving early (perhaps while the poor were still working) and enjoying a large meal together with fine food. The poor would arrive later with their own scanty food (possibly for the 'symposium'). The bread and wine of the Lord's Supper were brought together and taken at the end of the meal (rather than the bread at the beginning and the wine at the end, with the meal in between, as it happened at the last supper).

- The rich and poor were eating at the same time, but bringing their own food - the rich eating and drinking well, with meat and delicacies, and the poor with scanty food, perhaps only bread. Although the rich opened their houses to the poor they did so in a way which emphasised the social divisions. There was over-indulgence on the part of the rich, and feelkings of envy on the part of the poor.

In the earlier messages I've written in this series I think it's been clear that there is a pattern in the way the Gospel-writers record the meals where our Lord was present. Either by example or through His words the Lord taught that meals should reflect the abundant generosity and graciousness of God. We should invite to our tables the poor, the sick, the disabled, the 'sinners', the 'unclean' and the disenfranchised. They should be places where we celebrate and share the forgiveness of God, and look forward as a kind of foretaste to the messianic banquet in the age to come. The Corinthian practice created a division in the church between the rich and poor, which was contrary to this message of Jesus. It was therefore not "the Lord's supper" because it went so violently against the spirit of His message.

The Lord's table was inclusive; the Corinthian table was exclusive. The Lord's table brought together people from opposite ends of the social spectrum; the Corinthian table created a division in the Body of Christ. The Lord's table celebrated forgiveness. The Corinthian table created envy. The Lord's table proclaimed His self-giving, demonstrated in His death; the Corinthian table was self-centred. At the Lord's table people examined themselves; at the Corinthian table they judged each other.

In determining how the Lord intended us to "do this", and in deciding how the church today should celebrate the Lord's Supper, we should keep in mind these important factors:

- Our Lord's pattern of table-fellowship was to be welcoming, inviting, inclusive, forgiving and generous in spirit.

- The last supper was a meal which began and ended with prayers of thanksgiving, focussing on the self-giving of our Lord.

- The early church met together in homes to share a meal and to celebrate 'the Lord's supper' on a regular basis.

- The celebration of the Lord's supper in the early church probably followed the pattern of "grace before meals" (over the bread), the meal, and then "grace after meals" (over the cup). The Corinthians appear to have departed from this practice and were strongly rebuked by Paul.

- The last supper was a festive meal. The early church may have celebrated 'the Lord's supper' as both an annual festive event, and as a regular (usually weekly) coming together for a meal.

- By remembering Jesus in eating bread and drinking wine, and giving thanks, any 'ordinary meal' is sanctified. If it arises out of the same spirit which characterised our Lord's table fellowship then an 'ordinary meal' becomes 'the Lord's Supper'.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

The Lord's table (11) - the Last Supper and the sacraments/ordinances

Did Jesus intend that bread and wine should be used as sacraments?* What was the reason for using these two 'emblems' and how should the church observe communion today?

Christadelphians, as with many Protestant groups, believe that Christians should observe the two ordinances of Baptism and Breaking of Bread as 'commandments of Christ'. The purpose of this message is to look at what Jesus intended when He said, at the last supper, "do this in remembrance of me".

The synoptists (Matthew, Mark and Luke) are unanimous that the last supper was a Passover meal, and Paul provides some additional commentary (in 1 Corinthians) which confirms this. The following list shows some of the elements of the Passover meal which are referred to in the Gospels or in Paul's letter.

How did Jesus understand His own death?

Jesus' primary message during His ministry was about the Kingdom of God (see my earlier messages about the Gospel of the Kingdom, commencing with 'The Gospel in the Gospels'). Jesus taught that people could be set free by faith. He taught that God is forgiving and wants to give us the Kingdom. He modeled a life of dependance on God and enjoying freedom within that relationship. He never taught that atonement or reconciliation would come through His crucifixion, and although He predicted His death by execution on several occasions He never once referred to His death as the means of salvation.

There is only one saying of Jesus in the whole of the Gospels which might appear to contradict this: what's commonly called 'the ransom saying' in Mark 10:45 and Matt 20:28. "The Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many." What did Jesus mean? The context of this saying is a dispute between the sons of Zebedee about who would be greatest in the kingdom of God. Jesus called His disciples together and taught them about true greatness, culminating in this saying where He sets Himself forward as an example of selfless service and clarifies what He meant earlier about drinking from the cup he drinks and being baptised with the baptism with which He is baptised. The Greek word lyton, translated as 'ransom', was used of the price paid to free slaves and the related verb lytoo was used of deliverance in a general way. When used metaphorically it does not imply that payment is given to any individual, although the term stresses that freedom is accomplished at a great cost. When Jesus said the Son of Man came to "give his life" he is not referring solely to His death. The words immediately preceeding this - the Son of Man came to serve - reveals that He has in mind a life of service, and not simply the culmination of that life.

During the last supper Jesus referred to His blood as 'the blood of the covenant', referring to the sacrifice which sealed a covenant. He is undoubtedly referring to the blood with which Moses sealed the covenant in Exodus 24:8 and the new covenant of Jeremiah 31:31-34. The words in Jeremiah refer to the community of God's people receiving God's law in their hearts and minds and is contrasted with the exodus from Egypt ("It will not be like the covenant I made with their forefathers when I took them by the hand to lead them out of Egypt"). Jesus undoubtedly had Jeremiah's words in mind at this Passover-celebration from Egypt, and Jeremiah revealed that the new covenant will be different to the old, as the new community of the covenant-people will be different from the old community. The emphasis again is on the Kingdom which Jesus is inaugurating.

For Jesus the 'last supper' was the first of a new type of Passover - a remembrance of the deliverance from the bondage of sin and the institution of the new covenant and a new community of covenant-people. The Kingdom of God had come and this meal was a foretaste of the Messianic banquet of which he had spoken so many times.

The bread and wine are symbols of His body and blood - not a dead body or the loss of blood which would extinguish a life, but His whole life given over completely in service to God. They speak of a lifetime of service in the Kingdom of God, not a few hours on the cross. The purpose of re-enacting this meal "in remembrance of me" is to recall His life-long devotion, His teachings and ethics, and His central message of the Kingdom as the community of God's people. The Eucharist, or Communion, is a celebration of thanksgiving (the word 'Eucharist' comes from the Greek eucharistia meaning 'thansgiving' which recalls the words of Luke 22:17-19 "he gave thanks". 'Eucharist' is one of the oldest Christian words for the service of communion, and was used in the Didache). It is a thanksgiving for His life of service which culminated in a supreme sacrifice, His teachings, the deliverance from sin, God's gift of salvation, the new covenant which Jesus inaugurated, and the Kingdom-community over which He is King.

The Passover lamb was not sacrificed as an atonement for sins - there were other offerings which brought atonement, but not this one. It's purpose was to recall the blood which was painted on the doorposts of the Israelities in Egypt so that the angel of death would 'pass over' and not slay their firstborn sons. Hence it was a symbol of God's protection. So Paul's reference to Christ as "our Passover lamb" was not to His death as an atonement, but to the protection given to the people of God and their covenant-relationship with Him.

There is no suggestion, either in the Gospels or in Paul's writings, that there is any sacramental benefit from re-enacting the last supper, unless we understand it in the sense that the act of remembering keeps us connected to the source of grace. We are forgiven because of God's abundant generosity, and because of His righteousness, not because of our observance of rituals. Our forgiveness is not dependant on celebrating Communion, and does not come through it. Nor is forgiveness withheld because we might share the bread and wine with someone who is 'unworthy'. Paul emphasises that if anyone eats or drinks "in an unworthy manner" he eats and drinks judgment "on himself" (1 Cor 11:27-29). There is no hint of "guilt by association" when it comes to the Lord's table.

In my next message I want to suggest how I think Jesus intended us to "do this in remembrance" and how the church could do this today.

* A sacrament, in the Western tradition, is often defined as an outward, visible sign that conveys an inward, spiritual grace (and to Protestants the word conveys would be understood in the sense that it is a visible symbol or reminder of invisible grace). While the Catholic and Orthodox churches believe there are seven sacraments, most Protestant churches consider there are only two, Baptism and the Eucharist (or Communion), and these are sometimes called ordinances rather than sacraments. Denominations which do not believe in sacramental theology may nevertheless refer to some ordinances as a "sacrament" in an effort to underscore their belief in the sanctity of the institution (and I have occasionally heard the word 'sacrament' used in Christadelphian meetings to refer to the 'breaking of bread', although it is uncommon).

Christadelphians, as with many Protestant groups, believe that Christians should observe the two ordinances of Baptism and Breaking of Bread as 'commandments of Christ'. The purpose of this message is to look at what Jesus intended when He said, at the last supper, "do this in remembrance of me".

The synoptists (Matthew, Mark and Luke) are unanimous that the last supper was a Passover meal, and Paul provides some additional commentary (in 1 Corinthians) which confirms this. The following list shows some of the elements of the Passover meal which are referred to in the Gospels or in Paul's letter.

- Jesus referred to the meal as the Passover: ""I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer" (Luke 22:15).

- Paul refers to the use of unleavened bread (1 Cor 5:7-8) as an aspect of the Passover meal with significance to Christian Communion.

- The 'cup of blessing' (1 Cor 10:16 KJV or 'cup of thansgiving' NIV) was the third of four cups of wine which were drank at Passover (the four cups were the cup of sanctification, the cup of wrath, the cup of blessing or redemption, and the cup of acceptance or praise). Luke specifically refers to two of these cups (Luke 22:17 and 20).

- Paul refers to the lamb which was a central feature of the Passover meal in his comment that "Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed" (1 Cor 5:7 NIV - the Greek word pascha strictly speaking means simply 'Passover' [so KJV et al]. It may also refer to the Passover lamb or meal and clearly has the meaning of 'lamb' here as it "has been sacrificed").

- Jesus used the words "do this in remembrance of me" (1 Cor 11:24-25 and Luke 22:19). The purpose of the Passover was that "you may remember the time of your departure from Egypt" (Deut 16:3).

- The purpose of the Passover for Israel was that they might remember their deliverance from Egypt, and Jesus refers to the wine as a symbol of His "blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins" (Matt 26:28) and may have been making an allusion to deliverance from sin as a connection to Passover.

How did Jesus understand His own death?

Jesus' primary message during His ministry was about the Kingdom of God (see my earlier messages about the Gospel of the Kingdom, commencing with 'The Gospel in the Gospels'). Jesus taught that people could be set free by faith. He taught that God is forgiving and wants to give us the Kingdom. He modeled a life of dependance on God and enjoying freedom within that relationship. He never taught that atonement or reconciliation would come through His crucifixion, and although He predicted His death by execution on several occasions He never once referred to His death as the means of salvation.

There is only one saying of Jesus in the whole of the Gospels which might appear to contradict this: what's commonly called 'the ransom saying' in Mark 10:45 and Matt 20:28. "The Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many." What did Jesus mean? The context of this saying is a dispute between the sons of Zebedee about who would be greatest in the kingdom of God. Jesus called His disciples together and taught them about true greatness, culminating in this saying where He sets Himself forward as an example of selfless service and clarifies what He meant earlier about drinking from the cup he drinks and being baptised with the baptism with which He is baptised. The Greek word lyton, translated as 'ransom', was used of the price paid to free slaves and the related verb lytoo was used of deliverance in a general way. When used metaphorically it does not imply that payment is given to any individual, although the term stresses that freedom is accomplished at a great cost. When Jesus said the Son of Man came to "give his life" he is not referring solely to His death. The words immediately preceeding this - the Son of Man came to serve - reveals that He has in mind a life of service, and not simply the culmination of that life.

During the last supper Jesus referred to His blood as 'the blood of the covenant', referring to the sacrifice which sealed a covenant. He is undoubtedly referring to the blood with which Moses sealed the covenant in Exodus 24:8 and the new covenant of Jeremiah 31:31-34. The words in Jeremiah refer to the community of God's people receiving God's law in their hearts and minds and is contrasted with the exodus from Egypt ("It will not be like the covenant I made with their forefathers when I took them by the hand to lead them out of Egypt"). Jesus undoubtedly had Jeremiah's words in mind at this Passover-celebration from Egypt, and Jeremiah revealed that the new covenant will be different to the old, as the new community of the covenant-people will be different from the old community. The emphasis again is on the Kingdom which Jesus is inaugurating.

For Jesus the 'last supper' was the first of a new type of Passover - a remembrance of the deliverance from the bondage of sin and the institution of the new covenant and a new community of covenant-people. The Kingdom of God had come and this meal was a foretaste of the Messianic banquet of which he had spoken so many times.

The bread and wine are symbols of His body and blood - not a dead body or the loss of blood which would extinguish a life, but His whole life given over completely in service to God. They speak of a lifetime of service in the Kingdom of God, not a few hours on the cross. The purpose of re-enacting this meal "in remembrance of me" is to recall His life-long devotion, His teachings and ethics, and His central message of the Kingdom as the community of God's people. The Eucharist, or Communion, is a celebration of thanksgiving (the word 'Eucharist' comes from the Greek eucharistia meaning 'thansgiving' which recalls the words of Luke 22:17-19 "he gave thanks". 'Eucharist' is one of the oldest Christian words for the service of communion, and was used in the Didache). It is a thanksgiving for His life of service which culminated in a supreme sacrifice, His teachings, the deliverance from sin, God's gift of salvation, the new covenant which Jesus inaugurated, and the Kingdom-community over which He is King.

The Passover lamb was not sacrificed as an atonement for sins - there were other offerings which brought atonement, but not this one. It's purpose was to recall the blood which was painted on the doorposts of the Israelities in Egypt so that the angel of death would 'pass over' and not slay their firstborn sons. Hence it was a symbol of God's protection. So Paul's reference to Christ as "our Passover lamb" was not to His death as an atonement, but to the protection given to the people of God and their covenant-relationship with Him.

There is no suggestion, either in the Gospels or in Paul's writings, that there is any sacramental benefit from re-enacting the last supper, unless we understand it in the sense that the act of remembering keeps us connected to the source of grace. We are forgiven because of God's abundant generosity, and because of His righteousness, not because of our observance of rituals. Our forgiveness is not dependant on celebrating Communion, and does not come through it. Nor is forgiveness withheld because we might share the bread and wine with someone who is 'unworthy'. Paul emphasises that if anyone eats or drinks "in an unworthy manner" he eats and drinks judgment "on himself" (1 Cor 11:27-29). There is no hint of "guilt by association" when it comes to the Lord's table.

In my next message I want to suggest how I think Jesus intended us to "do this in remembrance" and how the church could do this today.

Sunday, February 19, 2006

The Lord's table (10) - who was at the Last Supper?

We have artists like Leonardo Da Vinci to thank for giving the impression that the 'Last Supper' was eaten at a table with Jesus seated in the centre. Da Vinci, however, was wrong.

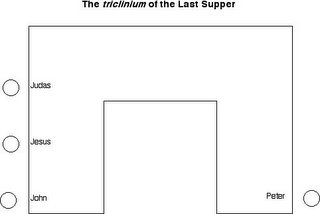

The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) are clear that the last supper was the Jewish Passover meal and that it was eaten in a reclining position, as was customary. According to the practice at the time, the table would have been close to the floor and the participants reclined on cushions. Alfred Edershem (The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah) and other scholars have explained how the guests would have been seated. The meal would have been eaten at a three-sided table called a triclinium.

Edersheim carefully analysed the conversations and other recorded details of the last supper and demonstrated that we can actually work out the seating positions of four participants at the meal.

I won't go into the details here as to how we know this seating arrangement, but I can provide the details later if anyone is interested.

Another important thing which Edersheim brings to our attention is the number of people who would have been celebrating the Passover in Jerusalem in the time of Christ. This was one of the obligatory feasts when a large number of pilgrims would have been in the city.

It was necessary that the meal be eaten indoors, in groups, and following certain procedures which were carefully laid down in the Law and by tradition. Jerusalem on Passover night was a crowded city and space was at a premium. (By the way, if you have any doubts that the Last Supper was actually the Passover, Matthew, Mark and Luke were unanimous that it was - Mark even specifies that it was on the day when the Paasover lambs were sacrificed [Mk 14:12] - and the comment in John 18:28 that appears to contradict this can easily be reconciled with the Synoptists once we understand the terminology related to the Feasts of Israel. John refers to a claim by the Chief Priests that defilement would make it impossible for them to eat the Passover. By the time of Christ Passover day and the feast of unleavened bread which followed Passover were referred to collectively as "Passover". John's reference is to the priests being unable to join in with the festival meals during the week-long "Passover" festival, and not to the Passover meal itself which had already happened the night before. Any other interpretation puts John in conflict with Matthew, Mark and Luke).

To find a vacant "large upper room" (Mark 14:15; Luke 22:12) in Jerusalem at Passover would have well nigh on impossible. At best they would have arranged to have shared a large room, with other groups of between 10 and 20 people (the numbers specified by Jewish law). For several families or groups to have gathered together in one large room, and then to have eaten the meal around their individual tables would have been such a common practice that the Jewish Law (the Mishnah) explained the regulations for such cases.

Luke refers to a group of 120 "all together in one place" in Jerusalem a short time after (Acts 2:1). Elsewhere he refers to the Jerusalem church meeting at the home of John Mark (Acts 12:12) and there is some circumstantial evidence that the last supper was held in the same home (let me know if you'd like me to provide it).

It is extremely likely that Jesus and the Twelve celebrated Passover in a large room which could have accomodated 120 people. They probably shared the room with several other groups, possibly with other disciples, especially the ones who travelled around the country with them. This helps to explain why private conversations between Peter and John, John and Jesus, and Jesus and Judas , were not heard by the others present. There would have been considerable background noise.

Of course, I cannot "prove" that there were more than 13 present at the last supper, but I don't need to. The number of people present at the meal does not alter anything I've previously said about the nature of this meal. However, those who insist that this meal was a small, exclusive, private gathering have a bit of explaining to do.

Throughout the Gospels we find different types of meals where Jesus was present: from meals with disciples or friends to meals with His religious enemies; meals with crowds of thousands, to small, intimate gatherings. Each setting has lessons to teach us. One thing that was common to them all was that Jesus turned no one away. He taught His disciples and the exclusivist Pharisees to open their meals and celebrations to all who were disenfranchised, rejected, despised and considered 'unclean'. At His last supper he welcomed the one who would soon betray him, a disciple who was about to deny knowing him, and friends who were arguing about which of them should have the most prominent positions, in denial of all He had taught them about servanthood. In fact, within hours all of them would desert him (Matthew 26:56; Mark 14:50). Even knowing that he was about to eat with men who were weak, wavering, even treacherous, men who would deny knowing him or even betray him, he welcomed them all and greatly desired to have this meal with them (Luke 22:15). Such was our Lord's inclusiveness.

Friday, February 17, 2006

The Night He Was Betrayed

Just as some 'background' to the posts on the Last Supper here is an article which I wrote several years ago and which was published in The Christadelphian (August 1987, p 284).

The purpose of this article is to draw together the threads which run through the Gospels in relation to the betrayal of Jesus; to link together some apparently unrelated happenings and to piece together the details of the plot to kill Jesus. We shall examine Judas’ motives and the attitudes of the other disciples and Jesus himself, to him. We hope to solve some of the puzzles which surround this fateful night and will see why it will always be remembered as “the night he was betrayed” (1 Cor. 11: 23).

What Motivated Judas to Betray Jesus?

Judas’ disillusionment may have begun about twelve months before this final, fateful Passover. Following the feeding of the 5,000 the people tried to make Jesus their king and the Twelve had probably joined forces with the crowd, or possibly even led them, in their zeal to see Jesus enthroned in his rightful place as the Son of David and Messiah of Israel. This is made plain enough by the fact that Jesus “constrained” his disciples to leave the scene while he dismissed the crowd (Matt 14:22, A.V., cp. John 6:15); the Twelve were apparently a hindrance to him and, for the time being, he was better off with them well out of the way. The next day some of the same crowd came to hear Jesus teach in the synagogue at Capernaum, but they found his teachings either incomprehensible or unacceptable and “many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him” (John 6:60, 66). Aware that the Twelve had been sympathetic with the Messianic expectations of the crowd, Jesus asked if they too wanted to leave and singled out Judas for special mention: “Have I not chosen you, the Twelve? Yet one of you is a devil! (He meant Judas who later was to betray him)” (John 6: 67-71). Why this special reference at this time to Judas? Had he been a ringleader in the attempt to make Jesus a king, or did he too wish to leave with the others who were disillusioned?

But disillusionment alone was not enough to cause Judas to betray Jesus. Pride had to be combined with it. This happened at Bethany when again Judas was the ringleader or spokesman for the Twelve in objecting to Mary’s waste of very expensive perfume, and was then himself rebuked for failing to understand that it was “a beautiful thing” which she had done (Matt. 26: 6-13; cp. John 12:1-8). Matthew records this incident between the plot by the chief priests to kill Jesus and Judas’ visit to them, and Mark also records Judas’ offer to betray Jesus immediately after the Bethany incident. This was not simply to get the chronology right but because the Bethany incident was central to the betrayal. Luke’s version, when compared with the other synoptic writers, confirms this:

Luke’s mention of Satan, in the light of this comparison, seems to be referring somehow to the Bethany incident. It could mean that it was at this particular time that Judas completely surrendered to his human nature and was angered by his humiliation to the extent of wanting to seek vengeance.

John gives us another motive: Judas was a thief and helped himself to their common purse (John 12:6). Certainly this was a reason for his objection to this waste of expensive perfume. Although none of the Gospel writers actually give Judas’ avarice as a reason for the betrayal, it is possible that Paul had it in mind when he wrote: “The love of money is a root of all kinds of evil. Some people, eager for money, have wandered from the faith and pierced themselves with many griefs” (1 Tim. 6:10). Admittedly, 30 silver coins was not an enormous sum (about four months’ wages for a labourer) (1) , but Mark’s and Luke’s accounts that the chief priests “promised to give him money”, when compared with Matthew’s record that they “counted out for him 30 silver coins”, could easily imply that they paid him a deposit with more to follow when the prisoner was secured.

The Conspiracy with the Sanhedrin

The chief priests and elders “plotted to arrest Jesus in some cunning way and kill him” (Matt. 26:4). Before Jesus arrived in Jerusalem for the Passover they “had given orders that if anyone found out where Jesus was, he should report it so that they might arrest him” (John 11:57). However, they made one stipulation: “But not during the Feast, or thee may be a riot among the people” (Matt. 26:5). Luke adds that “they were afraid of the people” (Luke 22:2). There was another reason why they wanted to avoid crowds. On three earlier occasions attempts had been made to kill Jesus and he had escaped (Luke 4:16-30; John 8:59; 10:22-39). On the two later occasions, both in the temple, Jesus’ escape was made possible by slipping through the crowds. Here was how Judas could help: “He watched for an opportunity to hand Jesus over to them when no crowd was present” (Luke 22:6).

The chief priests had made one restriction only - “not during the Feast” - and yet, on Judas’ advice, they set aside this one requirement. As it turned out, Judas was to obtain information of such importance that they would arrest Jesus at what had been earlier considered to be the worst possible time. To discover what this information was, we need to look at what transpired in the upper room.

The Upper Room

Soon after Jesus and the Twelve entered the upper room a dispute arose among the disciples “as to which of them was considered to be the greatest” (Luke 22:24). It was not the first time; a similar dispute had erupted a few days earlier over who would sit on Jesus’ left and right hands in his glory (Matt. 20:20-28; Mark 10:35-45). The dispute may have re-erupted over the same issue, this time prompted by the seating arrangements. It is apparent that John was on Jesus’ right (John 13:23-25) and Judas most likely was on his left. This is indicated by the fact that Judas was in close proximity to Jesus and their conversation was unheard by the others (2). These two disciples detected something about Jesus’ state of mind that night. While all four Gospel writers record Jesus’ prediction, “One of you will betray me”, John alone notes that while Jesus said this he was “troubled in spirit” (John 13:21). Judas also noticed this troubled disposition, and was later to find his knowledge useful.

The reaction of the others to Jesus’ prediction is remarkable. First “they looked on one another doubting of whom he spake” (John 13:22); secondly, “they began to question among themselves which of them it was” (Luke 22:23); and finally, “they began to be sorrowful and to say ‘Is it I?’ “ (Mark 14:19). They looked to themselves and focused on their own doubts and failings, rather than the faults of others. They may have thought that Jesus was referring to their earlier dispute as a kind of betrayal, a denial of his teaching and spirit. Paul no doubt alludes to their introspection when, in the context of the breaking of bread, he says “Let a man examine himself” (1 Cor. 11:28).

Peter asked John to find out from the Lord who would betray him. We hear nothing of Peter following up this request and asking John who it was who had been identified. Could it be that Jesus’ prediction of Peter’s denials had been understood by that apostle to be the answer to his question? Had his worst fears (“Is it I?”) been confirmed?

Judas’ Rendezvous with the Chief Priests

Jesus told John that he would identify the betrayer by giving him a piece of bread which he had dipped in the dish. He gave it to Judas. “As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him” (John 13:27). Had Judas heard what Jesus had said to John and was he now humiliated again by being identified in this way? If so, then his anger would have been rekindled and inflamed and Judas again surrendered to his human feelings.

He quickly left the room and went to the chief priests with some important information. “Jesus is in an unusual state of mind; he is ‘troubled in spirit’ and speaking of being betrayed; this would be the psychologically right moment to arrest Jesus because he would not resist or try to escape”. Such an approach by Judas seems to be indicated in Psalm 41 which is partially cited in John 13;18: “All my enemies whisper together against me; they imagine the worst for me, saying, ‘A vile disease has beset him; he will never get up from the place where he lies’. Even my close friend, whom I trusted, he who shared my bread, has lifted up his heel against me” (Psa. 41: 8-9).

Psalm 55 was written in the same historical context as Psalm 41: the rebellion of Absolom and Ahithophel’s betrayal of David. No doubt it equally applies to Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. “If an enemy were insulting me, I could endure it; if a foe were raising himself against me, I could hide from him. But it is you, a man like myself, my companion, my close friend, with whom I once enjoyed sweet fellowship as we walked with the throng at the house of God” (Psa. 55: 12-14). Was there any special way in which Jesus and Judas were “close friends” enjoying “sweet fellowship in the house of God”? It seems highly likely that Judas was the only Judaean among the Twelve (Iscariot is probably derived from Ish Kerioth - a man of Kerioth in Judaea) and therefore the only disciple likely to have had a formal religious education. This may have given him a good knowledge of Scripture, enabling him to discuss Scripture with Jesus on a different level to the others and therefore enjoying a special relationship. The expressions, “a man like myself, my companion, my close friend whom I trusted” certainly imply a special relationship, the last expression possibly referring to his office as treasurer, the only special office, as far the we are aware, to be held by any of the Twelve. Judas’ position on Jesus’ left at the last supper was probably a token of this relationship, as John’s position on Jesus’ right was because he was “the disciple he loved”. Judas was probably above suspicion as far as the other disciples were concerned; it certainly appears that they were blissfully unaware of his dealings with the common purse.

It is almost certain that it was this “vile disease”, this unusual depression or troubled spirit, which Judas used to persuade the chief priests to set aside their one stipulation that Jesus was not to be arrested during the Feast. They acted quickly and sent a delegation to Pilate to arrange a contingent of soldiers and a high-ranking Roman official to escort them to the place where Jesus was to be arrested (3). No doubt Pilate was also notified to expect a trial first thing the following morning before Jesus’ supporters could rally to his defence (4).

Gethsemane

In the meantime Jesus and the Eleven had left the upper room and gone to Gethsemane. Jesus’ troubled state of mind had become more intense, so that he would say, “My soul is exceeding sorrowful” (Matt. 26:38). He “offered up prayers and petitions, with loud cries and tears to the one who could save him from death” (Heb. 5:7).

“The Father heard; an angel there

Sustain’d the Son of God in prayer.”

Jesus’ prayer was heard and he was strengthened by an angel so that he could pray more earnestly (Luke 22: 43-44). As the Apostle records: “He endured for the joy that was set before him” (Heb. 12:2).

It was soon after this that Judas arrived with the Roman soldiers and members of the Sanhedrin. He had a pre-arranged signal for them: “The one I kiss is the man.” Why was such a signal necessary? Could not Judas simply point out the man to them? He must have wanted to avoid any appearance of complicity in the arrest so that he could retain his place among the Twelve - apparently believing that things were not over and that Jesus would simply be punished and released and no-one would know of his involvement. This signal would arouse no suspicion, being the usual greeting between a Rabbi and his disciple. The soldiers must have been instructed to observe from a distance and wait for a suitable time before coming out of the darkness (5). Judas was overly keen to give the impression that all was well. The Greek word used in the Gospels (kataphilein) means ‘to kiss tenderly or repeatedly, as one would a lover’. He would then have mingled with the other disciples who would be unaware that anything was wrong. By the time the soldiers came forward to arrest Jesus, Judas had made sure that his tracks had been covered. There is still one more clue leading to this conclusion.

At the High Priest’s House

John tells us that Peter and an unnamed disciple who was known to the High Priest followed Jesus to the house of Annas. It has often been assumed that this anonymous disciple was John himself, although the evidence for this is wanting. Why was John known to the High Priest? Why was not John’s Galilean accent noticed, as Peter’s was (Luke 22:59)? There was only one disciple whom we know for certain was known to the High Priest, and who had no Galilean accent - Judas! Judas had covered his tracks so well that Peter was still unaware of his involvement in Jesus’ arrest, and so the two of them followed Jesus to the High Priest’s house together. We do know for certain that Judas was there because he was present when the Sanhedrin came to its verdict and he saw Jesus condemned (Matt. 27:1-3).

Judas’ Remorse

Why was Judas suddenly “seized with remorse”? (Matt. 27:3). Events must have turned out very differently from what he anticipated. He could not have expected Jesus to be condemned to death; perhaps he only expected a flogging or similar treatment and his desire for vengeance because of his humiliation would have been satisified.

Judas had seen Jesus’ trial through to the end. He had started, with Peter, at the house of Annas. It was as Jesus was being led from Annas to the house of Caiaphas that he looked on Peter, who had in the meantime denied knowing him, and Peter ran from the scene in tears (Luke 22:61-62). Judas, however, followed as Jesus was interrogated by the Sanhedrin at Caiaphas’ house and then taken to the Temple precincts, where the ‘legal’ trial was conducted in the early hours of the morning (6) in the “Chamber of Hewn Stone”. It is likely that Judas was also at this final trial in the Temple precincts because it was into the actual Temple sanctuary itself (7) that Judas flung his thirty silver coins. The strong verb used to describe this act indicates that he did so in angry defiance (8).

Judas may even have felt tricked because the chief priests had not revealed their real intentions to him. Whatever he had hoped to achieve he did not want, nor did he expect, the death of Jesus. He knew Jesus to be underserving of death yet he was now faced with the terrible reality that Jesus was about to die because of him. “I have sinned, for I have betrayed innocent blood.” Judas, like Cain, felt that his sin was greater than he could be forgiven (Gen. 4:13, R.V. margin) and, like Ahithophel the betrayer of David (2 Sam. 17:23), he went and hanged himself.

Conclusion

We need to remember that from the beginning Jesus viewed Judas as a potential follower and disciple. They shared a closeness and developed a friendship as a result of their mutual interest in the things of God. But Judas was never a committed follower. His highest title for Jesus was “Rabbi” (Matt. 26:25), never “Lord”. He is a continual warning to all those half-hearted disciples who wish to be identified in some way with Jesus, his teachings or his followers, yet can never break free of their attachment to the world or their picture of what Jesus ought to be like. They eventually follow the same path of apostasy and “to their loss they crucify the Son of God afresh” (Heb. 6:6).

We need to realise that Judas’ apostasy was not sudden; it was a long process during which he nurtured his disillusionment and anger at being humiliated. Long before the betrayal he had turned from Jesus and sought satisfaction in wordly gain. His moment of realisation came at last when he discovered that his plans had gone horribly wrong and he had killed the one who had loved him. No one else was to blame; it was by his own choice that he left his apostolic ministry “to go where he belongs” (Acts 1:25).

Endnotes:

1. The stater or tetradrachmon was valued at 4 denarri. As a denarius was worth about a day’s wage (Matt. 20:1-16) Judas’ 30 silver coins would have been roughly equal to 120 days’ wages.

2. John 13:28, cp. Matt. 26:25. The others were not aware that Jesus had identified the betrayer to both John and Judas.

3. Gk. speira (John 18:3) is a technical term for a cohort of Roman soldiers and would not be used to describe Temple Police. Gk. chiliarch (John 18:12) is a military tribune, probably the commander of the Antonia fortress. The detachment of soldiers was large enough to warrant his presence at Jesus’ arrest.

4. John 18:29-34 indicates that the Sanhedrin had been so confident that Pilate would ratify their decision that they initially came without formally prepared charges. This implies that they had discussed the case with him the previous night and therefore did not expect formal charges to be required. Luke 23:1-2 pictures a scene of Jesus’ accusers hurriedly thinking up charges to satisfy Pilate. This provides the most likely explanation for the dreams had by Pilate’s wife (Matt. 27:19). She would have overheard the discussion late the previous night and her conscience had caused her to dream about the conspiracy to condemn “this righteous man”.

5. This is probably what is meant by the words, “Then the men stepped forward” (Matt. 26:50).

6. Matt 27:1 and Mark 15:1 record a trial “very early in the morning” when the Sanhedrin reached a decision. Luke records this trial fully (22:66; 23:1) saying that it was “at daybreak”. This was because the interrogation by the Sanhedrin during the night could not legally be called a trial.

7. Matt. 27:5. It was into the Naos, the actual Temple, rather than the Hieron, the Temple precincts, that Judas threw the money. He probably stood at the barrier between the Court of the Israelites and the Court of the Priests and threw the money across it into the Court of the Priests

8. Gk. rhipto has this meaning, according to R.V.G. Tasker in the Tyndale Commentary on Matthew.

“THE NIGHT HE WAS BETRAYED”

The purpose of this article is to draw together the threads which run through the Gospels in relation to the betrayal of Jesus; to link together some apparently unrelated happenings and to piece together the details of the plot to kill Jesus. We shall examine Judas’ motives and the attitudes of the other disciples and Jesus himself, to him. We hope to solve some of the puzzles which surround this fateful night and will see why it will always be remembered as “the night he was betrayed” (1 Cor. 11: 23).

What Motivated Judas to Betray Jesus?

Judas’ disillusionment may have begun about twelve months before this final, fateful Passover. Following the feeding of the 5,000 the people tried to make Jesus their king and the Twelve had probably joined forces with the crowd, or possibly even led them, in their zeal to see Jesus enthroned in his rightful place as the Son of David and Messiah of Israel. This is made plain enough by the fact that Jesus “constrained” his disciples to leave the scene while he dismissed the crowd (Matt 14:22, A.V., cp. John 6:15); the Twelve were apparently a hindrance to him and, for the time being, he was better off with them well out of the way. The next day some of the same crowd came to hear Jesus teach in the synagogue at Capernaum, but they found his teachings either incomprehensible or unacceptable and “many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him” (John 6:60, 66). Aware that the Twelve had been sympathetic with the Messianic expectations of the crowd, Jesus asked if they too wanted to leave and singled out Judas for special mention: “Have I not chosen you, the Twelve? Yet one of you is a devil! (He meant Judas who later was to betray him)” (John 6: 67-71). Why this special reference at this time to Judas? Had he been a ringleader in the attempt to make Jesus a king, or did he too wish to leave with the others who were disillusioned?

But disillusionment alone was not enough to cause Judas to betray Jesus. Pride had to be combined with it. This happened at Bethany when again Judas was the ringleader or spokesman for the Twelve in objecting to Mary’s waste of very expensive perfume, and was then himself rebuked for failing to understand that it was “a beautiful thing” which she had done (Matt. 26: 6-13; cp. John 12:1-8). Matthew records this incident between the plot by the chief priests to kill Jesus and Judas’ visit to them, and Mark also records Judas’ offer to betray Jesus immediately after the Bethany incident. This was not simply to get the chronology right but because the Bethany incident was central to the betrayal. Luke’s version, when compared with the other synoptic writers, confirms this:

| Matthew 26:1-16 |

| Mark 14:1-10 |

| Luke 22:1-6 |

Luke’s mention of Satan, in the light of this comparison, seems to be referring somehow to the Bethany incident. It could mean that it was at this particular time that Judas completely surrendered to his human nature and was angered by his humiliation to the extent of wanting to seek vengeance.

John gives us another motive: Judas was a thief and helped himself to their common purse (John 12:6). Certainly this was a reason for his objection to this waste of expensive perfume. Although none of the Gospel writers actually give Judas’ avarice as a reason for the betrayal, it is possible that Paul had it in mind when he wrote: “The love of money is a root of all kinds of evil. Some people, eager for money, have wandered from the faith and pierced themselves with many griefs” (1 Tim. 6:10). Admittedly, 30 silver coins was not an enormous sum (about four months’ wages for a labourer) (1) , but Mark’s and Luke’s accounts that the chief priests “promised to give him money”, when compared with Matthew’s record that they “counted out for him 30 silver coins”, could easily imply that they paid him a deposit with more to follow when the prisoner was secured.

The Conspiracy with the Sanhedrin

The chief priests and elders “plotted to arrest Jesus in some cunning way and kill him” (Matt. 26:4). Before Jesus arrived in Jerusalem for the Passover they “had given orders that if anyone found out where Jesus was, he should report it so that they might arrest him” (John 11:57). However, they made one stipulation: “But not during the Feast, or thee may be a riot among the people” (Matt. 26:5). Luke adds that “they were afraid of the people” (Luke 22:2). There was another reason why they wanted to avoid crowds. On three earlier occasions attempts had been made to kill Jesus and he had escaped (Luke 4:16-30; John 8:59; 10:22-39). On the two later occasions, both in the temple, Jesus’ escape was made possible by slipping through the crowds. Here was how Judas could help: “He watched for an opportunity to hand Jesus over to them when no crowd was present” (Luke 22:6).

The chief priests had made one restriction only - “not during the Feast” - and yet, on Judas’ advice, they set aside this one requirement. As it turned out, Judas was to obtain information of such importance that they would arrest Jesus at what had been earlier considered to be the worst possible time. To discover what this information was, we need to look at what transpired in the upper room.

The Upper Room

Soon after Jesus and the Twelve entered the upper room a dispute arose among the disciples “as to which of them was considered to be the greatest” (Luke 22:24). It was not the first time; a similar dispute had erupted a few days earlier over who would sit on Jesus’ left and right hands in his glory (Matt. 20:20-28; Mark 10:35-45). The dispute may have re-erupted over the same issue, this time prompted by the seating arrangements. It is apparent that John was on Jesus’ right (John 13:23-25) and Judas most likely was on his left. This is indicated by the fact that Judas was in close proximity to Jesus and their conversation was unheard by the others (2). These two disciples detected something about Jesus’ state of mind that night. While all four Gospel writers record Jesus’ prediction, “One of you will betray me”, John alone notes that while Jesus said this he was “troubled in spirit” (John 13:21). Judas also noticed this troubled disposition, and was later to find his knowledge useful.

The reaction of the others to Jesus’ prediction is remarkable. First “they looked on one another doubting of whom he spake” (John 13:22); secondly, “they began to question among themselves which of them it was” (Luke 22:23); and finally, “they began to be sorrowful and to say ‘Is it I?’ “ (Mark 14:19). They looked to themselves and focused on their own doubts and failings, rather than the faults of others. They may have thought that Jesus was referring to their earlier dispute as a kind of betrayal, a denial of his teaching and spirit. Paul no doubt alludes to their introspection when, in the context of the breaking of bread, he says “Let a man examine himself” (1 Cor. 11:28).

Peter asked John to find out from the Lord who would betray him. We hear nothing of Peter following up this request and asking John who it was who had been identified. Could it be that Jesus’ prediction of Peter’s denials had been understood by that apostle to be the answer to his question? Had his worst fears (“Is it I?”) been confirmed?

Judas’ Rendezvous with the Chief Priests

Jesus told John that he would identify the betrayer by giving him a piece of bread which he had dipped in the dish. He gave it to Judas. “As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him” (John 13:27). Had Judas heard what Jesus had said to John and was he now humiliated again by being identified in this way? If so, then his anger would have been rekindled and inflamed and Judas again surrendered to his human feelings.

He quickly left the room and went to the chief priests with some important information. “Jesus is in an unusual state of mind; he is ‘troubled in spirit’ and speaking of being betrayed; this would be the psychologically right moment to arrest Jesus because he would not resist or try to escape”. Such an approach by Judas seems to be indicated in Psalm 41 which is partially cited in John 13;18: “All my enemies whisper together against me; they imagine the worst for me, saying, ‘A vile disease has beset him; he will never get up from the place where he lies’. Even my close friend, whom I trusted, he who shared my bread, has lifted up his heel against me” (Psa. 41: 8-9).

Psalm 55 was written in the same historical context as Psalm 41: the rebellion of Absolom and Ahithophel’s betrayal of David. No doubt it equally applies to Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. “If an enemy were insulting me, I could endure it; if a foe were raising himself against me, I could hide from him. But it is you, a man like myself, my companion, my close friend, with whom I once enjoyed sweet fellowship as we walked with the throng at the house of God” (Psa. 55: 12-14). Was there any special way in which Jesus and Judas were “close friends” enjoying “sweet fellowship in the house of God”? It seems highly likely that Judas was the only Judaean among the Twelve (Iscariot is probably derived from Ish Kerioth - a man of Kerioth in Judaea) and therefore the only disciple likely to have had a formal religious education. This may have given him a good knowledge of Scripture, enabling him to discuss Scripture with Jesus on a different level to the others and therefore enjoying a special relationship. The expressions, “a man like myself, my companion, my close friend whom I trusted” certainly imply a special relationship, the last expression possibly referring to his office as treasurer, the only special office, as far the we are aware, to be held by any of the Twelve. Judas’ position on Jesus’ left at the last supper was probably a token of this relationship, as John’s position on Jesus’ right was because he was “the disciple he loved”. Judas was probably above suspicion as far as the other disciples were concerned; it certainly appears that they were blissfully unaware of his dealings with the common purse.

It is almost certain that it was this “vile disease”, this unusual depression or troubled spirit, which Judas used to persuade the chief priests to set aside their one stipulation that Jesus was not to be arrested during the Feast. They acted quickly and sent a delegation to Pilate to arrange a contingent of soldiers and a high-ranking Roman official to escort them to the place where Jesus was to be arrested (3). No doubt Pilate was also notified to expect a trial first thing the following morning before Jesus’ supporters could rally to his defence (4).

Gethsemane

In the meantime Jesus and the Eleven had left the upper room and gone to Gethsemane. Jesus’ troubled state of mind had become more intense, so that he would say, “My soul is exceeding sorrowful” (Matt. 26:38). He “offered up prayers and petitions, with loud cries and tears to the one who could save him from death” (Heb. 5:7).

“The Father heard; an angel there

Sustain’d the Son of God in prayer.”

Jesus’ prayer was heard and he was strengthened by an angel so that he could pray more earnestly (Luke 22: 43-44). As the Apostle records: “He endured for the joy that was set before him” (Heb. 12:2).

It was soon after this that Judas arrived with the Roman soldiers and members of the Sanhedrin. He had a pre-arranged signal for them: “The one I kiss is the man.” Why was such a signal necessary? Could not Judas simply point out the man to them? He must have wanted to avoid any appearance of complicity in the arrest so that he could retain his place among the Twelve - apparently believing that things were not over and that Jesus would simply be punished and released and no-one would know of his involvement. This signal would arouse no suspicion, being the usual greeting between a Rabbi and his disciple. The soldiers must have been instructed to observe from a distance and wait for a suitable time before coming out of the darkness (5). Judas was overly keen to give the impression that all was well. The Greek word used in the Gospels (kataphilein) means ‘to kiss tenderly or repeatedly, as one would a lover’. He would then have mingled with the other disciples who would be unaware that anything was wrong. By the time the soldiers came forward to arrest Jesus, Judas had made sure that his tracks had been covered. There is still one more clue leading to this conclusion.

At the High Priest’s House

John tells us that Peter and an unnamed disciple who was known to the High Priest followed Jesus to the house of Annas. It has often been assumed that this anonymous disciple was John himself, although the evidence for this is wanting. Why was John known to the High Priest? Why was not John’s Galilean accent noticed, as Peter’s was (Luke 22:59)? There was only one disciple whom we know for certain was known to the High Priest, and who had no Galilean accent - Judas! Judas had covered his tracks so well that Peter was still unaware of his involvement in Jesus’ arrest, and so the two of them followed Jesus to the High Priest’s house together. We do know for certain that Judas was there because he was present when the Sanhedrin came to its verdict and he saw Jesus condemned (Matt. 27:1-3).

Judas’ Remorse

Why was Judas suddenly “seized with remorse”? (Matt. 27:3). Events must have turned out very differently from what he anticipated. He could not have expected Jesus to be condemned to death; perhaps he only expected a flogging or similar treatment and his desire for vengeance because of his humiliation would have been satisified.

Judas had seen Jesus’ trial through to the end. He had started, with Peter, at the house of Annas. It was as Jesus was being led from Annas to the house of Caiaphas that he looked on Peter, who had in the meantime denied knowing him, and Peter ran from the scene in tears (Luke 22:61-62). Judas, however, followed as Jesus was interrogated by the Sanhedrin at Caiaphas’ house and then taken to the Temple precincts, where the ‘legal’ trial was conducted in the early hours of the morning (6) in the “Chamber of Hewn Stone”. It is likely that Judas was also at this final trial in the Temple precincts because it was into the actual Temple sanctuary itself (7) that Judas flung his thirty silver coins. The strong verb used to describe this act indicates that he did so in angry defiance (8).

Judas may even have felt tricked because the chief priests had not revealed their real intentions to him. Whatever he had hoped to achieve he did not want, nor did he expect, the death of Jesus. He knew Jesus to be underserving of death yet he was now faced with the terrible reality that Jesus was about to die because of him. “I have sinned, for I have betrayed innocent blood.” Judas, like Cain, felt that his sin was greater than he could be forgiven (Gen. 4:13, R.V. margin) and, like Ahithophel the betrayer of David (2 Sam. 17:23), he went and hanged himself.

Conclusion

We need to remember that from the beginning Jesus viewed Judas as a potential follower and disciple. They shared a closeness and developed a friendship as a result of their mutual interest in the things of God. But Judas was never a committed follower. His highest title for Jesus was “Rabbi” (Matt. 26:25), never “Lord”. He is a continual warning to all those half-hearted disciples who wish to be identified in some way with Jesus, his teachings or his followers, yet can never break free of their attachment to the world or their picture of what Jesus ought to be like. They eventually follow the same path of apostasy and “to their loss they crucify the Son of God afresh” (Heb. 6:6).

We need to realise that Judas’ apostasy was not sudden; it was a long process during which he nurtured his disillusionment and anger at being humiliated. Long before the betrayal he had turned from Jesus and sought satisfaction in wordly gain. His moment of realisation came at last when he discovered that his plans had gone horribly wrong and he had killed the one who had loved him. No one else was to blame; it was by his own choice that he left his apostolic ministry “to go where he belongs” (Acts 1:25).

Endnotes:

1. The stater or tetradrachmon was valued at 4 denarri. As a denarius was worth about a day’s wage (Matt. 20:1-16) Judas’ 30 silver coins would have been roughly equal to 120 days’ wages.

2. John 13:28, cp. Matt. 26:25. The others were not aware that Jesus had identified the betrayer to both John and Judas.

3. Gk. speira (John 18:3) is a technical term for a cohort of Roman soldiers and would not be used to describe Temple Police. Gk. chiliarch (John 18:12) is a military tribune, probably the commander of the Antonia fortress. The detachment of soldiers was large enough to warrant his presence at Jesus’ arrest.

4. John 18:29-34 indicates that the Sanhedrin had been so confident that Pilate would ratify their decision that they initially came without formally prepared charges. This implies that they had discussed the case with him the previous night and therefore did not expect formal charges to be required. Luke 23:1-2 pictures a scene of Jesus’ accusers hurriedly thinking up charges to satisfy Pilate. This provides the most likely explanation for the dreams had by Pilate’s wife (Matt. 27:19). She would have overheard the discussion late the previous night and her conscience had caused her to dream about the conspiracy to condemn “this righteous man”.

5. This is probably what is meant by the words, “Then the men stepped forward” (Matt. 26:50).

6. Matt 27:1 and Mark 15:1 record a trial “very early in the morning” when the Sanhedrin reached a decision. Luke records this trial fully (22:66; 23:1) saying that it was “at daybreak”. This was because the interrogation by the Sanhedrin during the night could not legally be called a trial.

7. Matt. 27:5. It was into the Naos, the actual Temple, rather than the Hieron, the Temple precincts, that Judas threw the money. He probably stood at the barrier between the Court of the Israelites and the Court of the Priests and threw the money across it into the Court of the Priests

8. Gk. rhipto has this meaning, according to R.V.G. Tasker in the Tyndale Commentary on Matthew.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

The Lord's table (9) - the Last Supper (continued)

I've been asked to write some more material on the theme of our Lord's table fellowship practices, especially in relation to the 'Last Supper'.

I plan to write something on 3 things in particular:

1. Who was at the last supper? It's important to answer this question because some people claim that the intimacy of the occasion, the limited number (our Lord and 12 'guests'), and the secrecy surrounding the preparation of the meal indicate that when it comes to celebrating communion our Lord set an example of exclusivism (which should consequently be imitated by the church, so the argument goes). This flies in the face of Jesus' pattern of inclusivism, so the question of who was there is important.

2. The Last Supper and the sacraments. Did Jesus intend that bread and wine should be used as sacraments? What was the reason for using these two 'emblems' and how should the church observe communion today?

3. This was obviously no ordinary meal. So what was so special about it, why was it different, and how, and what are we meant to learn from it?

I'm going to be very busy next week so I will try to post as much as I can beforehand. My apologies in advance if I don't get to write much. I also haven't forgotten the other series I've started but not yet finished. It will all come together, eventually, by God's grace.

I plan to write something on 3 things in particular:

1. Who was at the last supper? It's important to answer this question because some people claim that the intimacy of the occasion, the limited number (our Lord and 12 'guests'), and the secrecy surrounding the preparation of the meal indicate that when it comes to celebrating communion our Lord set an example of exclusivism (which should consequently be imitated by the church, so the argument goes). This flies in the face of Jesus' pattern of inclusivism, so the question of who was there is important.

2. The Last Supper and the sacraments. Did Jesus intend that bread and wine should be used as sacraments? What was the reason for using these two 'emblems' and how should the church observe communion today?

3. This was obviously no ordinary meal. So what was so special about it, why was it different, and how, and what are we meant to learn from it?

I'm going to be very busy next week so I will try to post as much as I can beforehand. My apologies in advance if I don't get to write much. I also haven't forgotten the other series I've started but not yet finished. It will all come together, eventually, by God's grace.

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Christadelphian authoritarianism today

I gave some examples in recent posts of the trend towards authoritarianism in the Christadelphian movement. However, these weren't isolated events in history - there is strong evidence of authoritarianism in some parts of Christadelphianism today.

Here is just one example. The Adelaide Suburban Young People recently sent a letter to their member ecclesias emphasising the need to ensure their young people "conform" (their word) to certain dress standards which they will "enforce at the door" (their expression). Their letter is below, with my emphasis.

It's made clear that the young people will not be permitted to think for themselves, and that even their parents opinions will not be taken into consideration. The role of parents has been taken over by the authorities in the youth group. "There may be parents that are unsupportive of our position on these matters but the accepted standards are not negotiable." The rules have been made and will be enforced. Even visitors from unaffiliated ecclesias will be "subject to the same rules."

No wonder that their young people are restless and inattentive in the classes when those in control are demanding adherence to "rules" rather than providing a message which is stimulating, relevant and life-changing.

Here is just one example. The Adelaide Suburban Young People recently sent a letter to their member ecclesias emphasising the need to ensure their young people "conform" (their word) to certain dress standards which they will "enforce at the door" (their expression). Their letter is below, with my emphasis.

Suburban Young Peoples’ Activities

16 January 2006

To the Recorders of the Adelaide Suburban, Glenlock, Mildura, Murray Bridge and Victor Harbor Ecclesias, and the IEAC.

Dear Brethren,

Loving greetings.

Over many years the Suburban Young Peoples Activities have become a valuable part of our Ecclesial life for young people. This facility provides a balance of activities to cater for their social and spiritual needs in a world that can give them nothing of lasting value. These activities draw together young people from a whole range of social and ecclesial circles, and yet united in a course of life, which can develop within them an appreciation for the ways of God. The worth of these activities in developing and promoting the spirit of the Truth in the Ecclesial environment both now and into the future is inestimable.

Amongst the young people, we have a wide variation of opinions on standards in relation to dress and attitude. Attention needs to be given to ensure our young people understand and conform to the accepted inter-ecclesial standards. This is nothing new and is something that has been constantly addressed in order to maintain a wholesome atmosphere in all that is done. Human nature is very persistent in attempting to promote “individual” standards based on current trends and not to conform to an agreed higher standard. It is essential to understand that the Suburban Young People’s environment is not the arena where these values are meant to be taught. They must be taught and promoted in the home environment, and supported by the Ecclesia so that they are naturally expected within the scope of the Suburban Young People’s activities. The wholesome atmosphere we have long enjoyed does not just happen, it has to be cultivated. Sadly non-compliance is often an issue and the work of hosting becomes exceedingly difficult when confronted by rebellion and the denial of respect for the rules and standards we ask our young people to respect.